Non-financial corporations can typically use two types of debt funding – bank loans and debt securities (e.g. bonds).

Choosing one of them, or the right mix, depends on a company’s maturity, the industry and its cyclicality, interest rates, and other factors. For instance, during the financial crisis of 2008-09, non-financial corporations in the euro zone reacted to tightening bank lending conditions by shifting their debt composition from bank loans towards debt securities. At the same time, the cost of market debt rose together with and exceeded the cost of bank debt1.

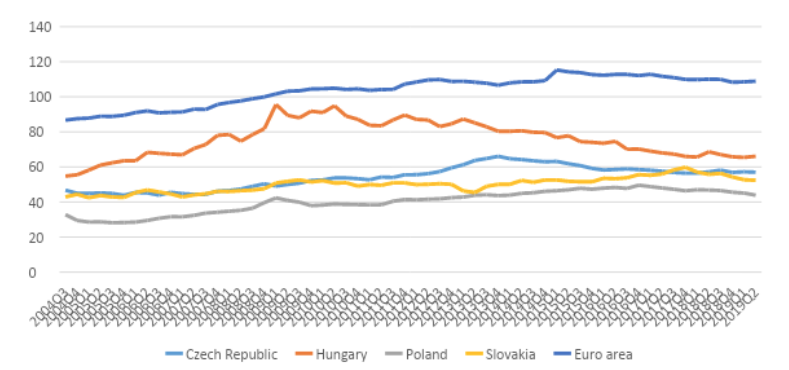

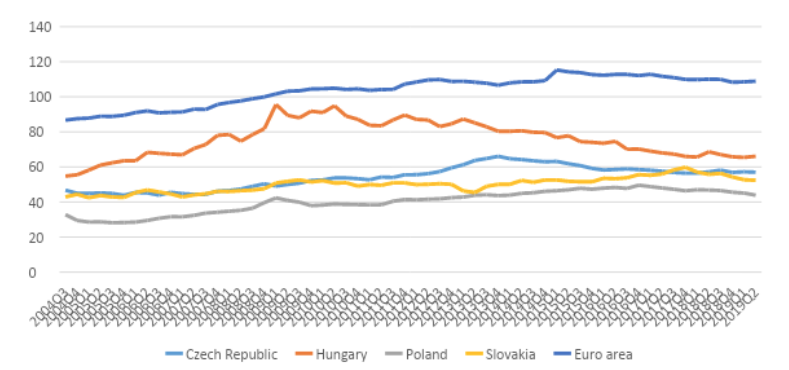

The corporate debt ratio in the euro area increased considerably over the last fifteen years, rising to 109% of the euro area’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 2Q 2019—but down from a peak of 115% in the first quarter of 2015. Total indebtedness of non-financial companies in the less developed countries of the EU is considerably lower: the corporate debt ratio in Visegrad countries varies between 44% to 66% as of 2Q 2019, as indicated by the chart below.

Exhibit 1: Debt of non-financial corporations as a ratio of GDP2 Although the composition of corporate debt varies among countries, bank loans are by far the more widely used instrument. On average, 68% of total euro area corporate debt consists of bank loans. In the Visegrad Four countries, loans dominate the composition of corporate debt to an even greater degree: debt securities (corporate bonds) have a relatively low share (9%) in the debt structure within the euro area (with an exclusion of France). In the Visegrad Four counties, a share of debt securities is even below 9% of total corporate debt. In Hungary, debt securities account for only 1% of total corporate debt—the second lowest in the EU, ranking slightly higher than Romania. One can only speculate that this might be due to a highly developed banking sector, and perhaps a dearth of potential Hungarian issuers.

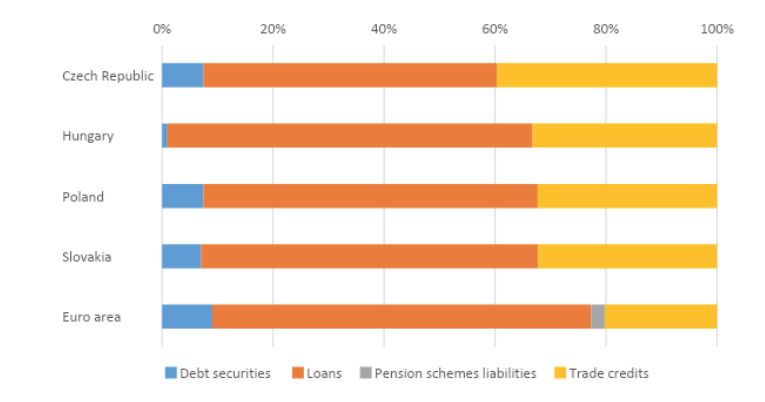

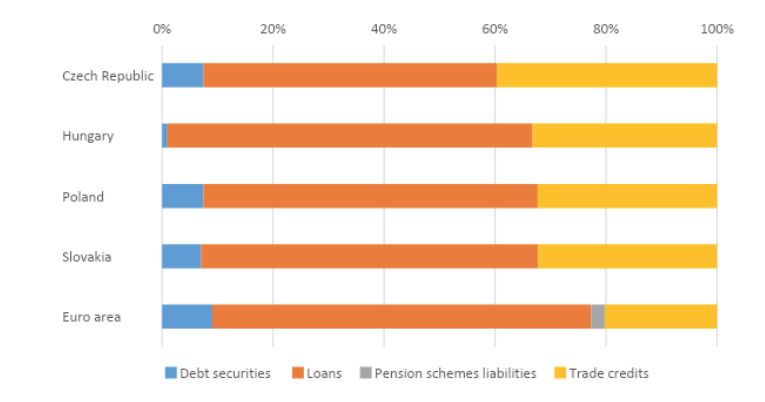

Although the composition of corporate debt varies among countries, bank loans are by far the more widely used instrument. On average, 68% of total euro area corporate debt consists of bank loans. In the Visegrad Four countries, loans dominate the composition of corporate debt to an even greater degree: debt securities (corporate bonds) have a relatively low share (9%) in the debt structure within the euro area (with an exclusion of France). In the Visegrad Four counties, a share of debt securities is even below 9% of total corporate debt. In Hungary, debt securities account for only 1% of total corporate debt—the second lowest in the EU, ranking slightly higher than Romania. One can only speculate that this might be due to a highly developed banking sector, and perhaps a dearth of potential Hungarian issuers.

Exhibit 2: Composition of corporate debt at the end of 2Q 20193 * Trade credits refer to trade credits (e.g. goods purchased on account) and advances of non-financial corporations, all maturities

* Trade credits refer to trade credits (e.g. goods purchased on account) and advances of non-financial corporations, all maturities

There is a positive correlation between economic development and levels of outstanding bonds of nonfinancial corporations, as a percentage of GDP; in the more developed countries of the European Union, not only the total indebtedness of the companies, but also the volume of their funds raised on the bond market substantially exceeds that observed in the less developed countries4. The robust corporate bond market can act as a source of stability, especially in periods of financial instability, when the freezing up of bank credit is common. Moreover, the corporate bond market can create competition for bank loans, pushing cost of borrowing for non-financial corporations lower and forming more attractive funding options.

In Hungary, debt financing is especially focused on the banking sector. Over time, it may be expected that Hungary will tend to converge towards European trends, with more financing to come from the corporate bond market. In order to increase liquidity of the corporate bond market, the Hungarian National Bank (Magyar Nemzeti Bank – MNB) launched the Bond Funding for Growth Scheme (BGS) on 1 July 2019. The MNB has committed a facility of HUF 300 billion (approximately EUR 90 million) whereby the central bank will purchase bonds with at least B+ ratings issued by domestic non-financial corporations as well as securities backed by corporate loans. On October 24, 2019 Alteo, alternative energy company, raised almost HUF 9 billion from the sale of corporate bonds issued within the framework of this program5.

Bank interest rates for loans to corporations with an original maturity of over two years are lowest in Hungary and Slovakia. The latter is the only member of the Visegrad group that is also simultaneously a member of the euro zone.

Exhibit 3: Bank interest rates – loans to corporations with an original maturity of over two years in Visegrad countries6 The above graph conveys that Slovakian interest rates have been consistently lower than those of other Visegrad countries. This may be attributed to Slovakia belonging to the Euro zone: a serious competitive advantage for Slovak corporations. It goes to show that Hungary, Poland and Czech Republic joining the Euro zone could also serve to increase competitiveness of corporations in those countries.

The above graph conveys that Slovakian interest rates have been consistently lower than those of other Visegrad countries. This may be attributed to Slovakia belonging to the Euro zone: a serious competitive advantage for Slovak corporations. It goes to show that Hungary, Poland and Czech Republic joining the Euro zone could also serve to increase competitiveness of corporations in those countries.

The corporate debt ratio in the euro area increased considerably over the last fifteen years, rising to 109% of the euro area’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 2Q 2019—but down from a peak of 115% in the first quarter of 2015. Total indebtedness of non-financial companies in the less developed countries of the EU is considerably lower: the corporate debt ratio in Visegrad countries varies between 44% to 66% as of 2Q 2019, as indicated by the chart below.

Exhibit 1: Debt of non-financial corporations as a ratio of GDP2

Although the composition of corporate debt varies among countries, bank loans are by far the more widely used instrument. On average, 68% of total euro area corporate debt consists of bank loans. In the Visegrad Four countries, loans dominate the composition of corporate debt to an even greater degree: debt securities (corporate bonds) have a relatively low share (9%) in the debt structure within the euro area (with an exclusion of France). In the Visegrad Four counties, a share of debt securities is even below 9% of total corporate debt. In Hungary, debt securities account for only 1% of total corporate debt—the second lowest in the EU, ranking slightly higher than Romania. One can only speculate that this might be due to a highly developed banking sector, and perhaps a dearth of potential Hungarian issuers.

Although the composition of corporate debt varies among countries, bank loans are by far the more widely used instrument. On average, 68% of total euro area corporate debt consists of bank loans. In the Visegrad Four countries, loans dominate the composition of corporate debt to an even greater degree: debt securities (corporate bonds) have a relatively low share (9%) in the debt structure within the euro area (with an exclusion of France). In the Visegrad Four counties, a share of debt securities is even below 9% of total corporate debt. In Hungary, debt securities account for only 1% of total corporate debt—the second lowest in the EU, ranking slightly higher than Romania. One can only speculate that this might be due to a highly developed banking sector, and perhaps a dearth of potential Hungarian issuers.Exhibit 2: Composition of corporate debt at the end of 2Q 20193

* Trade credits refer to trade credits (e.g. goods purchased on account) and advances of non-financial corporations, all maturities

* Trade credits refer to trade credits (e.g. goods purchased on account) and advances of non-financial corporations, all maturitiesThere is a positive correlation between economic development and levels of outstanding bonds of nonfinancial corporations, as a percentage of GDP; in the more developed countries of the European Union, not only the total indebtedness of the companies, but also the volume of their funds raised on the bond market substantially exceeds that observed in the less developed countries4. The robust corporate bond market can act as a source of stability, especially in periods of financial instability, when the freezing up of bank credit is common. Moreover, the corporate bond market can create competition for bank loans, pushing cost of borrowing for non-financial corporations lower and forming more attractive funding options.

In Hungary, debt financing is especially focused on the banking sector. Over time, it may be expected that Hungary will tend to converge towards European trends, with more financing to come from the corporate bond market. In order to increase liquidity of the corporate bond market, the Hungarian National Bank (Magyar Nemzeti Bank – MNB) launched the Bond Funding for Growth Scheme (BGS) on 1 July 2019. The MNB has committed a facility of HUF 300 billion (approximately EUR 90 million) whereby the central bank will purchase bonds with at least B+ ratings issued by domestic non-financial corporations as well as securities backed by corporate loans. On October 24, 2019 Alteo, alternative energy company, raised almost HUF 9 billion from the sale of corporate bonds issued within the framework of this program5.

Bank interest rates for loans to corporations with an original maturity of over two years are lowest in Hungary and Slovakia. The latter is the only member of the Visegrad group that is also simultaneously a member of the euro zone.

Exhibit 3: Bank interest rates – loans to corporations with an original maturity of over two years in Visegrad countries6

The above graph conveys that Slovakian interest rates have been consistently lower than those of other Visegrad countries. This may be attributed to Slovakia belonging to the Euro zone: a serious competitive advantage for Slovak corporations. It goes to show that Hungary, Poland and Czech Republic joining the Euro zone could also serve to increase competitiveness of corporations in those countries.

The above graph conveys that Slovakian interest rates have been consistently lower than those of other Visegrad countries. This may be attributed to Slovakia belonging to the Euro zone: a serious competitive advantage for Slovak corporations. It goes to show that Hungary, Poland and Czech Republic joining the Euro zone could also serve to increase competitiveness of corporations in those countries.

1Corporate Debt Structure and the Financial Crisis by Fiorella De Fiore and Harald Uhlig

2European Central Bank, Debt excluding trade credit of non-financial corporations as a ratio of GDP

3European Central Bank

4Considerations behind the launch of the Bond funding for Growth Scheme (BGS) and main features of the Program

5Alteo issues bonds of nearly 9 billion HUF (Közel 9 milliárd forintos kötvénykibocsátás az Alteonál) by portflio.hu

6European Central Bank, percentages per annum; period averages; secondary market yields of government bonds with maturities of close to ten years

2European Central Bank, Debt excluding trade credit of non-financial corporations as a ratio of GDP

3European Central Bank

4Considerations behind the launch of the Bond funding for Growth Scheme (BGS) and main features of the Program

5Alteo issues bonds of nearly 9 billion HUF (Közel 9 milliárd forintos kötvénykibocsátás az Alteonál) by portflio.hu

6European Central Bank, percentages per annum; period averages; secondary market yields of government bonds with maturities of close to ten years