GDP growth (hence wealth creation and improved standards of living) are not possible without competitiveness. So the European track record on competitiveness is a genuine cause for concern.

This article breaks down the subject Europe’s declining relative competitiveness into four areas: (a) how to define competitiveness? (b) what stats might be used, and what do the stats actually show? (c) what might explain this decline? (d) what is the prognosis for the future and how might this decline be reversed?

(a) How to define competitiveness?

There is no one standard definition of competitiveness. In researching this article, I came across quite a few definitions. The one I liked best: “Competitiveness, at regional and/or country level, is based on the ability to compete in the global market. It can be understood as a set of institutions, policies and factors, embedded in networks of innovation and entrepreneurship, able to determine the level of productivity of an economy, wealth creation, job creation, capture and return of investment, economic growth and social welfare.”

(b) What stats might be used, and what do the stats actually show?

There are many stats often used to describe competitiveness; here are some of the most popular:

Global Competitiveness Score (GCI) as calculated by the World Economic Forum declined from 70.9 in 2011 to 66.8 in 2020.

GDP growth over a longer time period is an indication of competitiveness. According to the World Bank, GDP growth from 2011-2020 was as follows:

Start-up Activity. In 2020, there was $149.2 billion investment into start-ups, 67.9 billion in China, and only $42.8 billion in Europe. Europe greatly lags in the number of unicorns (e.g. start-ups that reach market capitalization of over $1 billion).

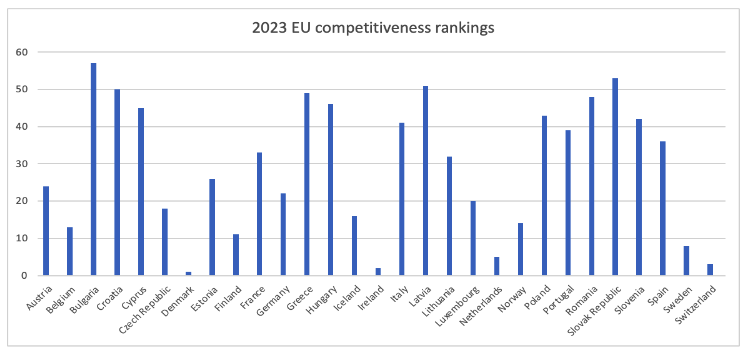

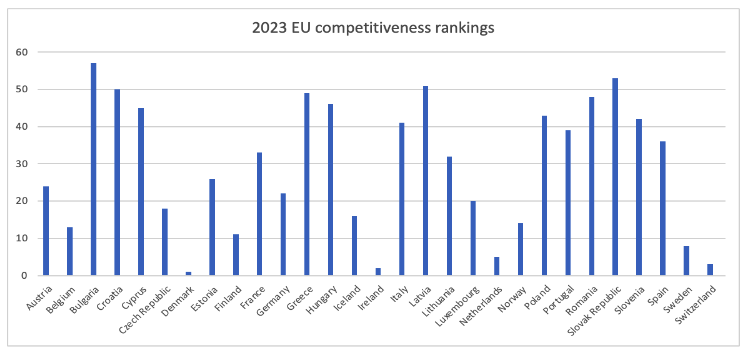

It is interesting to note that there are some fairly broad variations of competitiveness among European countries—see the chart below (noting that lower scores mean higher competitiveness):

(c) Explanation of the Decline

The reason perhaps most often given for declining European competitiveness is the decreasing participation of Europe in Global Value Chains (GVCs). This seems to be mostly at the expense of China’s increase. Furthermore, China’s vertical integration seems to be diminishing Europe’s ability to export into China. In many areas—such as automobiles, China has moved from merely supplying inputs to a fully finished product.

An amazing statistic: the number of graduates in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) in China equals those in Europe, the US and Japan put together.

A 2023 document by the European Commission (EC) comes to some pretty serious conclusions: “since the mid-1990s, the average productivity growth in the EU has been weaker than in other major economies, leading to an increasing gap in productivity levels. Demographic change adds further strains. Analyses show that the EU is also not at par with other parts of the world in some transversal technologies, trailing in all three dimensions of innovation, production and adoption and losing out on the latest technological developments that enable future growth.”

(d) What is the prognosis for the future and how might this decline be reversed?

The same document by the EC is optimistic that Europe’s relative competitiveness may begin to improve after 2030. Is this optimism well-founded? The factors listed in the previous paragraph are pretty hard to reverse, and the report is thin on specifics. Moreover, much of its strategy relies on deeper European integration (e.g. deepening and broadening the Single Market, creating a unified capital market, etc.) This may well happen—but it is a politically fraught exercise.

Meanwhile, we continue to read about examples where China eats European market share for breakfast. PwC, for example, recently forecast that due to China’s advances in electric vehicles and the increasing market share of electric vehicles, Europe may become a net importer of cars by 2025.

It is true that the purchasing power of the European market is vast and that Europe has an excellent competition policy. In my opinion, these are necessary but insufficient conditions for competitiveness. There are both top-down and bottom-up requirements to improve competitiveness:

The top-down element involves the EU and Governments enabling education, capital markets, legislative framework, etc.

The bottom-up element involves entrepreneurs creating winning innovation-based strategies accompanied by superb productivity gains and execution, a kind of industry-by-industry trench warfare to claw back market share. I do not see adequate discussion of the latter in the EC’s document, hence I cannot share the EC’s optimism about a post-2030 renaissance of competitiveness. (Meanwhile Europe loses the car industry by 2025…)

Unfortunately, if Europe’s relative competitiveness to China improves over the decade, it is likelier that this will be due to a slowing or implosion of China (see my earlier article on whether we are seeing Peak China), than a dramatic improvement in European competitiveness.

This article breaks down the subject Europe’s declining relative competitiveness into four areas: (a) how to define competitiveness? (b) what stats might be used, and what do the stats actually show? (c) what might explain this decline? (d) what is the prognosis for the future and how might this decline be reversed?

(a) How to define competitiveness?

There is no one standard definition of competitiveness. In researching this article, I came across quite a few definitions. The one I liked best: “Competitiveness, at regional and/or country level, is based on the ability to compete in the global market. It can be understood as a set of institutions, policies and factors, embedded in networks of innovation and entrepreneurship, able to determine the level of productivity of an economy, wealth creation, job creation, capture and return of investment, economic growth and social welfare.”

(b) What stats might be used, and what do the stats actually show?

There are many stats often used to describe competitiveness; here are some of the most popular:

Global Competitiveness Score (GCI) as calculated by the World Economic Forum declined from 70.9 in 2011 to 66.8 in 2020.

GDP growth over a longer time period is an indication of competitiveness. According to the World Bank, GDP growth from 2011-2020 was as follows:

- Eurozone: 0.8%

- US: 2.1%

- China: 6.6%

Start-up Activity. In 2020, there was $149.2 billion investment into start-ups, 67.9 billion in China, and only $42.8 billion in Europe. Europe greatly lags in the number of unicorns (e.g. start-ups that reach market capitalization of over $1 billion).

It is interesting to note that there are some fairly broad variations of competitiveness among European countries—see the chart below (noting that lower scores mean higher competitiveness):

(c) Explanation of the Decline

The reason perhaps most often given for declining European competitiveness is the decreasing participation of Europe in Global Value Chains (GVCs). This seems to be mostly at the expense of China’s increase. Furthermore, China’s vertical integration seems to be diminishing Europe’s ability to export into China. In many areas—such as automobiles, China has moved from merely supplying inputs to a fully finished product.

An amazing statistic: the number of graduates in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) in China equals those in Europe, the US and Japan put together.

A 2023 document by the European Commission (EC) comes to some pretty serious conclusions: “since the mid-1990s, the average productivity growth in the EU has been weaker than in other major economies, leading to an increasing gap in productivity levels. Demographic change adds further strains. Analyses show that the EU is also not at par with other parts of the world in some transversal technologies, trailing in all three dimensions of innovation, production and adoption and losing out on the latest technological developments that enable future growth.”

(d) What is the prognosis for the future and how might this decline be reversed?

The same document by the EC is optimistic that Europe’s relative competitiveness may begin to improve after 2030. Is this optimism well-founded? The factors listed in the previous paragraph are pretty hard to reverse, and the report is thin on specifics. Moreover, much of its strategy relies on deeper European integration (e.g. deepening and broadening the Single Market, creating a unified capital market, etc.) This may well happen—but it is a politically fraught exercise.

Meanwhile, we continue to read about examples where China eats European market share for breakfast. PwC, for example, recently forecast that due to China’s advances in electric vehicles and the increasing market share of electric vehicles, Europe may become a net importer of cars by 2025.

It is true that the purchasing power of the European market is vast and that Europe has an excellent competition policy. In my opinion, these are necessary but insufficient conditions for competitiveness. There are both top-down and bottom-up requirements to improve competitiveness:

The top-down element involves the EU and Governments enabling education, capital markets, legislative framework, etc.

The bottom-up element involves entrepreneurs creating winning innovation-based strategies accompanied by superb productivity gains and execution, a kind of industry-by-industry trench warfare to claw back market share. I do not see adequate discussion of the latter in the EC’s document, hence I cannot share the EC’s optimism about a post-2030 renaissance of competitiveness. (Meanwhile Europe loses the car industry by 2025…)

Unfortunately, if Europe’s relative competitiveness to China improves over the decade, it is likelier that this will be due to a slowing or implosion of China (see my earlier article on whether we are seeing Peak China), than a dramatic improvement in European competitiveness.