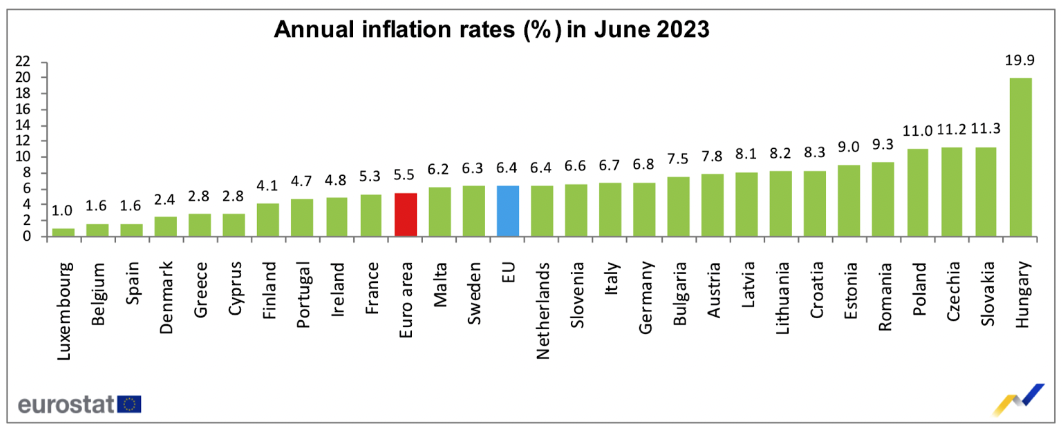

According to Eurostat’s release dated July 19, 2023, Hungary had by far the highest inflation in the Eurozone—not by a little—roughly triple the EU average and almost double the next highest countries

(Poland, Czechia and Slovakia).

The above chart shows Hungary as such a massive outlier, the analysis should be of interest also to non-Hungarian readers.

The above chart shows Hungary as such a massive outlier, the analysis should be of interest also to non-Hungarian readers.

In this article, we don’t look at general reasons for inflation, only at factors that make exceptionally high inflation a “Hungaricum”, (e.g. uniquely Hungarian feature). We outline six factors which are either unique to Hungary, or where Hungary has been a category “winner”:

The Government’s three main explanations for inflation are disingenuous:

The Government seems to have one foot on the accelerator (e.g. continuously high deficit spending), another foot on the brakes (the central bank’s interest rates rising to over 15%), and no clarity as to who is driving the vehicle. High uncertainty contributes to inflation.

Meanwhile, core inflation (e.g. excluding the most volatile prices such as energy and food) remains at 20.8% as of June 2023, meaning that inflation is becoming “baked in”. Wage growth is at 17.9% as of May, meaning that real wages declined in the first half of the year – a socially painful component of ongoing slow disinflation.

The poor, who by definition, spend a high percentage of income on foodstuffs and energy prices, are seeing their paychecks decimated by 29% food inflation and record energy prices. Retirees see their savings destroyed. As in most instances, it is the proverbial man-in-the-street who pays the price for poor governance.

We do not see a reversal of any of the above factors in the foreseeable future. Hence inflation in Hungary is likely to trend at a considerable premium to the EU. Nor does the Government’s objective or reaching a single digit inflation rate this year seem realistic.

The above chart shows Hungary as such a massive outlier, the analysis should be of interest also to non-Hungarian readers.

The above chart shows Hungary as such a massive outlier, the analysis should be of interest also to non-Hungarian readers.

In this article, we don’t look at general reasons for inflation, only at factors that make exceptionally high inflation a “Hungaricum”, (e.g. uniquely Hungarian feature). We outline six factors which are either unique to Hungary, or where Hungary has been a category “winner”:

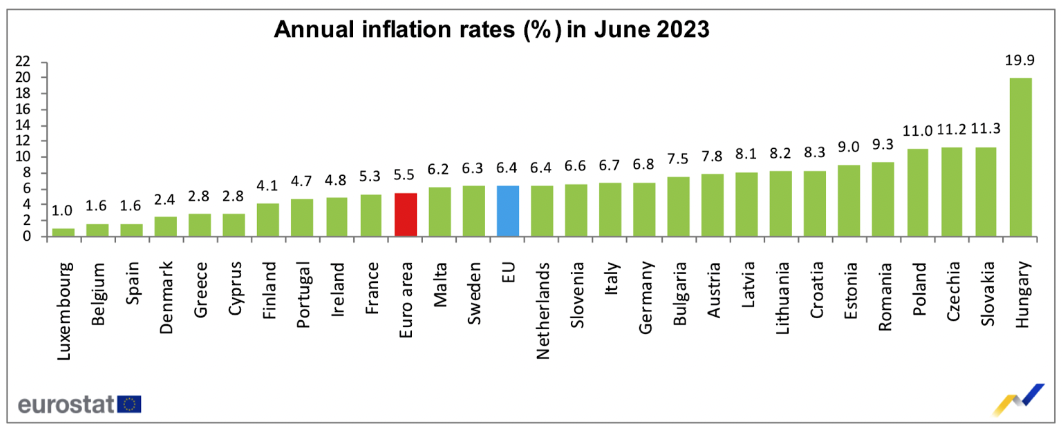

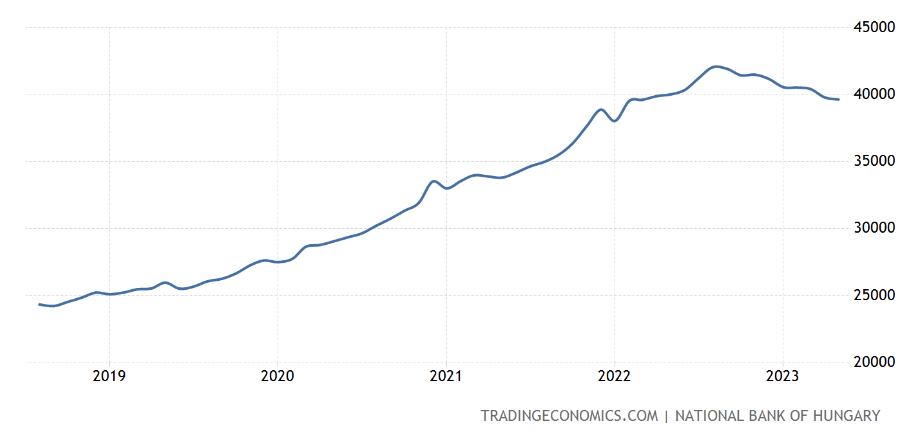

- 1. Devaluation as a strategy for competitiveness. Hungary is an open, export-driven economy, exporting primarily to the EU. Hungarian productivity growth (at about 0.8% per annum between 2010 and 2022) was roughly half the EU average. Hungary’s competitiveness rankings (according to IMD) plummeted last year from 39th to 46th place. The Hungarian Government has done little in the form of long-term investment into competitiveness, with severe underinvestment in education and healthcare. Hence the Government seems compelled to allow a continuous downward drift of the HUF to maintain competitiveness. Rather than declare a target exchange rate, the HUF is subject to unexpected market forces and speculation.

EUR to HUF Exchange Rate, 2019-2023

Given that the forint fell by about a quarter over the past five years, quite a few percentage points of inflation were imported every year.

Given that the forint fell by about a quarter over the past five years, quite a few percentage points of inflation were imported every year.

- 2. Deficit spending. In 2020, a high deficit was arguably justified by Covid-19. The 2021 continuation of high deficit spending, tax decreases and generous subsidies is best explained as electioneering for the 2022 elections. In 2022 the budgetary deficit remained unjustifiably high, at 6.2% of GDP.

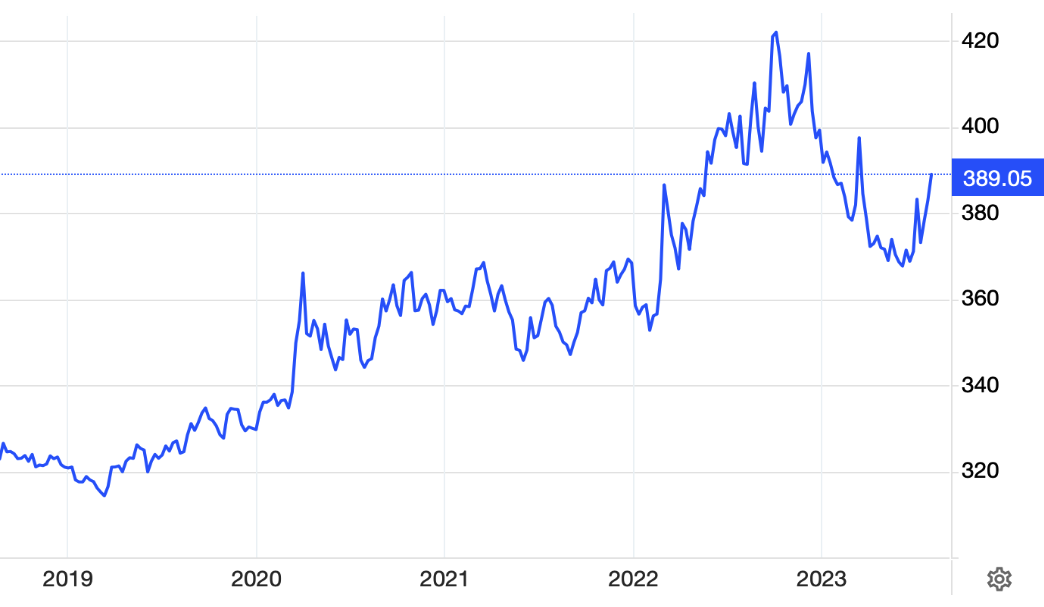

- 3. Money Supply has been growing rapidly over the past five years (except for a dip over the past year):

Money supply (M2) in Hungary, (HUF Billion)

- 4. Malinvestment. While investment usually has the effect of improving productivity, this does not apply where resources have been misallocated:

a, Government “prestige” investments such as soccer stadiums, or acquisitions of banks or telcos.

b, private sector investments that have been distorted by grant criteria or cheap loans. - 5. The Hungarian Central Bank recently announced massive losses (HUF 400 billion in 2022, with 2000 billion forecast for 2023), stemming from its balance sheet. There are a myriad of programs with heavily subsidized loans, while debt service costs have risen inexorably. The Government recently declared its intention to rewrite central banking law to ensure losses are not borne by the central budget, allowing the Central Bank several years to reverse these losses. A central bank may function with losses or even negative capital, but this may erode trust in monetary authorities, particularly in a country with a BBB/BBB-minus risk rating.

- 6. Corruption is inflationary. Transparency International has just ranked Hungary the most corrupt country in the European Union. The Government pays a corruption-inflated price for much of its procurement.

The Government’s three main explanations for inflation are disingenuous:

- The Ukrainian War. This affects all V4 countries. It cannot possibly serve to explain why inflation in Hungary is higher!

- High Energy Prices. At close to recent peak energy prices, Hungary to locked into long-term energy contracts with Russia. (The contracts themselves are confidential). While wholesale energy prices tumbled throughout Europe over the past 6-9 months, retail natural gas and electricity prices have remained distressingly high in Hungary.

- Multinationals Price Gouging. Once again, multinationals are also present in other V4 and EU countries, hence this cannot explain why inflation is so much Hungary. (Hungarian multinational food retailers and energy firms do, however, pay punitive sector taxes which contribute to inflation).

The Government seems to have one foot on the accelerator (e.g. continuously high deficit spending), another foot on the brakes (the central bank’s interest rates rising to over 15%), and no clarity as to who is driving the vehicle. High uncertainty contributes to inflation.

Meanwhile, core inflation (e.g. excluding the most volatile prices such as energy and food) remains at 20.8% as of June 2023, meaning that inflation is becoming “baked in”. Wage growth is at 17.9% as of May, meaning that real wages declined in the first half of the year – a socially painful component of ongoing slow disinflation.

The poor, who by definition, spend a high percentage of income on foodstuffs and energy prices, are seeing their paychecks decimated by 29% food inflation and record energy prices. Retirees see their savings destroyed. As in most instances, it is the proverbial man-in-the-street who pays the price for poor governance.

We do not see a reversal of any of the above factors in the foreseeable future. Hence inflation in Hungary is likely to trend at a considerable premium to the EU. Nor does the Government’s objective or reaching a single digit inflation rate this year seem realistic.