Germany’s economic miracle over the past few decades has been based on two major economic assumptions: cheap Russian energy and open access to an ever-growing Chinese market.

Both of these assumptions have recently been proven very wrong, thanks to the war in Ukraine and Chinese threats of invading Taiwan.

Due to loss of cheap energy and diminished trade with China, the German economic engine has been sputtering—many have forecast that it will crash. Given that Germany is the economic locomotive for Europe, particularly Central Europe, the outcome has implications beyond Germany. This article looks at each of the two economic assumptions separately and comes to the conclusion that Germany has handled these strong headwinds well, better than might have been expected a year ago.

a, Germany dependence on Russian energy

At the end of 2021, Russia supplied 55% of Germany’s gas requirements. This was reduced to 26 % by mid-2022. Germany aims to replace all energy imports from Russia by mid-2024. There is a similar trend for oil.

This turnaround is perhaps best symbolized by Germany’s construction of a Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) terminal in eight months. This is the type of grand and rapid infrastructure project one would expect of the Chinese. In Europe, eight months, under normal circumstances, would probably not even suffice for design and permitting!

The Germans also had to re-open coal-fired power plants and extend the life of some nuclear reactors. But the fact that Germany didn’t have to freeze in the dark or ration energy is quite remarkable. Norway replaced Russia as Germany’s largest source of gas imports.

Of course, Germany experienced double digit energy price increases, resulting in a roughly 14% decrease in gas consumption in 2022. The German Government is also spending some EUR 65 billion to shield consumers and industries, thus limiting economic pain to a still manageable level. The German chemical industry was particularly hard hit, with companies like BASF shuttering plants in Germany, building new ones abroad.

A combination of new sources (LNG, Norway), putting more reliance on existing sources (coal, uranium), and using the good old price mechanism to cut demand has proven very effective in keeping the lights on.

b, Germany’s dependence on Chinese exports

China has been Germany’s largest export market for most of the past decade. Recently, the Scholz Government declared China a strategic competitor. Germans have become very cognizant of their dependency on China (e.g. exports, rare earths, solar panels, etc.). A report by the German Economic Institute recently stated: “ The German economy is much more dependent on China than the other way round.” While 2022 saw a big increase in German export dependency on China, the trend seems to have reversed itself in 2023, most likely related to geopolitical tensions over Taiwan.

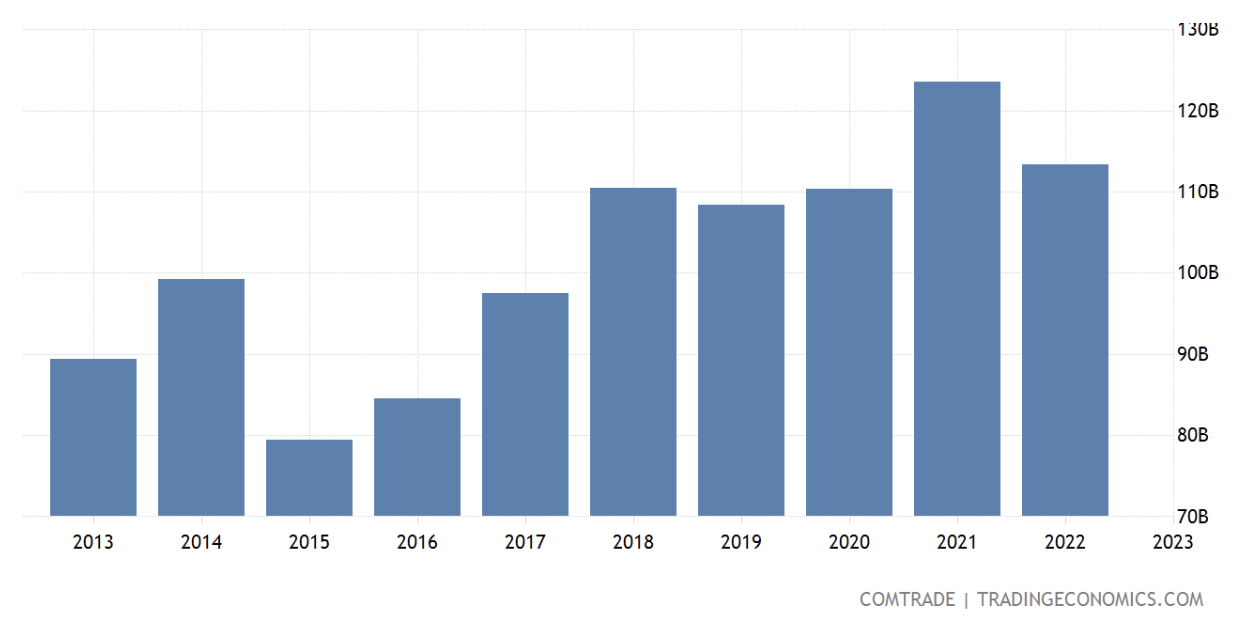

Exhibit 1: German Exports to China ($ billion)

In the first four months of 2023, German exports to China slipped by a further 11% (compared to the prior year), driven mostly by the Chinese perception that Germany is towing the US line. This will cause stress for companies like Volkswagen, which sells more cars in China than any other non-Chinese brand.

The German Government is still wrestling with how to deal with China. While they want to push through a minority Chinese investment into a container port in Hamburg (deemed by the Germans a strategic asset), they are also considering screening German companies investing into China, to protect flow of sensitive technology. A China Strategy has been postponed until after a national security review is completed. It seems, inevitable, however, that the Germans (like the EU) will attempt to “de-risk” its relationship with China. This is still open to definition—it will likely mean a host of measures, from not sharing sensitive technologies to diversifying trade relationships.

Should China simultaneously experience a “lost decade” similar to the one experienced by Japan in the 1990’s, (which I have argued in a previous article is a distinct possibility due to excessive indebtedness, property bubble, etc.) trade with China could decrease quite dramatically.

c, Summary

The German economy has undergone a mild recession, with 0.5% and 0.3% contractions in Q4 2022 and Q1 2023 respectively, and suffered a higher than EU average inflation rate recently. According to the IMF, the German economy is forecast to shrink by 0.1% in 2023. When you think about it—a mild recession is an exceptionally strong performance given these two very strong headwinds. Reducing dependence on Russian energy and Chinese exports are both one-off structural adjustments. Once the adjustments are made, the German economy will be less vulnerable, with good potential for growth to resume. The Germans have also set themselves the goal of becoming the most energy efficient country in the world. Thanks to their engineering prowess, this is a goal well within their grasp, and could become a pillar of long-term growth.

Due to loss of cheap energy and diminished trade with China, the German economic engine has been sputtering—many have forecast that it will crash. Given that Germany is the economic locomotive for Europe, particularly Central Europe, the outcome has implications beyond Germany. This article looks at each of the two economic assumptions separately and comes to the conclusion that Germany has handled these strong headwinds well, better than might have been expected a year ago.

a, Germany dependence on Russian energy

At the end of 2021, Russia supplied 55% of Germany’s gas requirements. This was reduced to 26 % by mid-2022. Germany aims to replace all energy imports from Russia by mid-2024. There is a similar trend for oil.

This turnaround is perhaps best symbolized by Germany’s construction of a Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) terminal in eight months. This is the type of grand and rapid infrastructure project one would expect of the Chinese. In Europe, eight months, under normal circumstances, would probably not even suffice for design and permitting!

The Germans also had to re-open coal-fired power plants and extend the life of some nuclear reactors. But the fact that Germany didn’t have to freeze in the dark or ration energy is quite remarkable. Norway replaced Russia as Germany’s largest source of gas imports.

Of course, Germany experienced double digit energy price increases, resulting in a roughly 14% decrease in gas consumption in 2022. The German Government is also spending some EUR 65 billion to shield consumers and industries, thus limiting economic pain to a still manageable level. The German chemical industry was particularly hard hit, with companies like BASF shuttering plants in Germany, building new ones abroad.

A combination of new sources (LNG, Norway), putting more reliance on existing sources (coal, uranium), and using the good old price mechanism to cut demand has proven very effective in keeping the lights on.

b, Germany’s dependence on Chinese exports

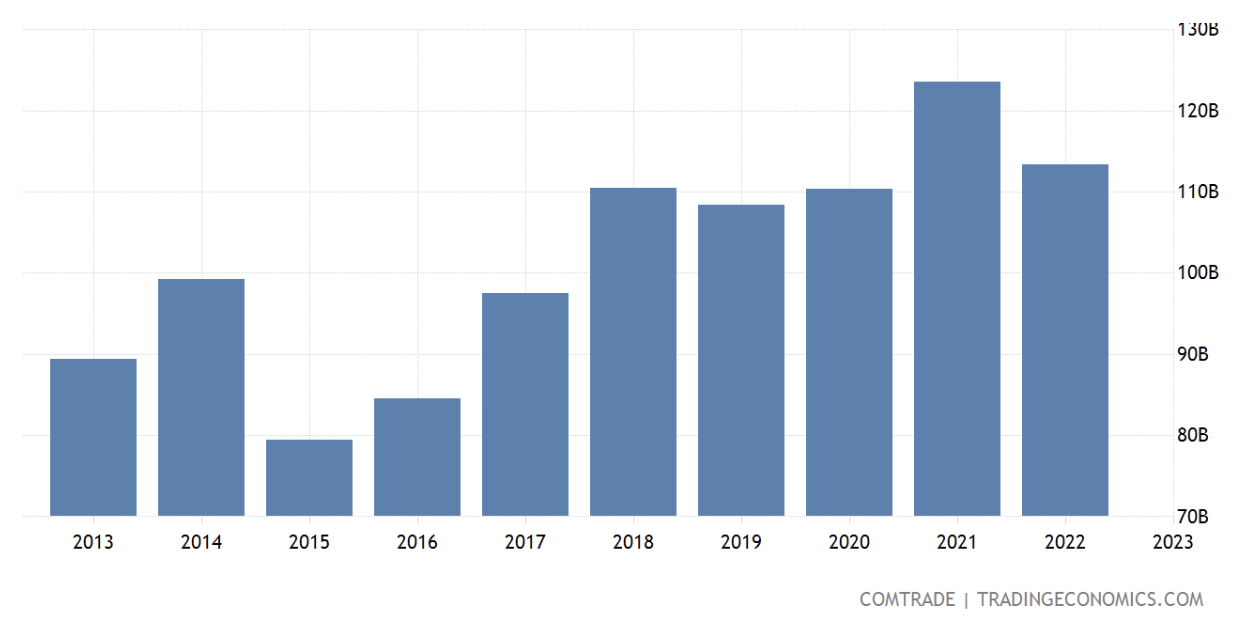

China has been Germany’s largest export market for most of the past decade. Recently, the Scholz Government declared China a strategic competitor. Germans have become very cognizant of their dependency on China (e.g. exports, rare earths, solar panels, etc.). A report by the German Economic Institute recently stated: “ The German economy is much more dependent on China than the other way round.” While 2022 saw a big increase in German export dependency on China, the trend seems to have reversed itself in 2023, most likely related to geopolitical tensions over Taiwan.

Exhibit 1: German Exports to China ($ billion)

In the first four months of 2023, German exports to China slipped by a further 11% (compared to the prior year), driven mostly by the Chinese perception that Germany is towing the US line. This will cause stress for companies like Volkswagen, which sells more cars in China than any other non-Chinese brand.

The German Government is still wrestling with how to deal with China. While they want to push through a minority Chinese investment into a container port in Hamburg (deemed by the Germans a strategic asset), they are also considering screening German companies investing into China, to protect flow of sensitive technology. A China Strategy has been postponed until after a national security review is completed. It seems, inevitable, however, that the Germans (like the EU) will attempt to “de-risk” its relationship with China. This is still open to definition—it will likely mean a host of measures, from not sharing sensitive technologies to diversifying trade relationships.

Should China simultaneously experience a “lost decade” similar to the one experienced by Japan in the 1990’s, (which I have argued in a previous article is a distinct possibility due to excessive indebtedness, property bubble, etc.) trade with China could decrease quite dramatically.

c, Summary

The German economy has undergone a mild recession, with 0.5% and 0.3% contractions in Q4 2022 and Q1 2023 respectively, and suffered a higher than EU average inflation rate recently. According to the IMF, the German economy is forecast to shrink by 0.1% in 2023. When you think about it—a mild recession is an exceptionally strong performance given these two very strong headwinds. Reducing dependence on Russian energy and Chinese exports are both one-off structural adjustments. Once the adjustments are made, the German economy will be less vulnerable, with good potential for growth to resume. The Germans have also set themselves the goal of becoming the most energy efficient country in the world. Thanks to their engineering prowess, this is a goal well within their grasp, and could become a pillar of long-term growth.