There is an old joke that the role of economic forecasters is to make astrologers look good. Forecasting GDP or inflation for the upcoming year with any degree of accuracy is virtually impossible

, as there are so many chance elements (war, pestilence, famine, etc.). In my view, it is far more important to understand economic drivers. This article will address a number of economic and financial drivers for 2023.

I see a continuation of some of the drivers I have been discussing in various articles over the past two years, namely (a) stubbornly high inflation, (b) to which Central Banks respond by keeping interest rates high or raising them further; which in turn (c) pushes most of the world into a recession (or worse, depression); (d) high interest rates and declining GDP growth strain financial markets. Let me address each of these in more detail. A twist of war (Ukraine, etc.), climate change (hurricanes, etc) and pestilence (Covid, etc. ) may contribute to high volatility.

a, Stubbornly high inflation

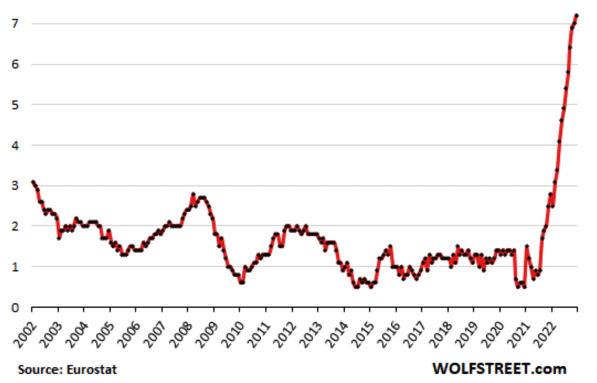

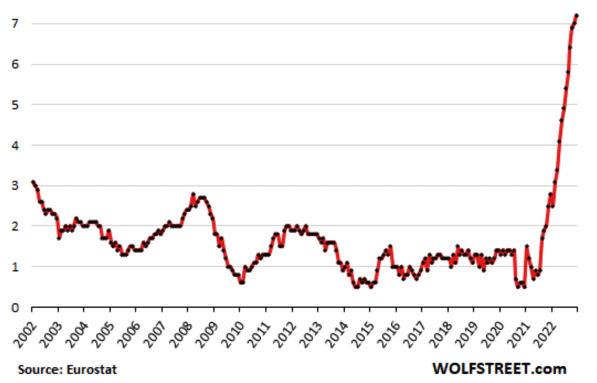

Eurostat has just released some extremely scary inflation numbers:

Exhibit 1: CPI without Energy, Eurozone, % Change from One Year Ago

Despite energy prices having moderated in the past months, inflation is going out of control in Europe. Negative demographics— including “the great resignation” (people falling out of the workforce far faster than normal)–means that wage pressures are extremely high, which feed into inflation in services. We are rapidly approaching the point where inflation expectations become entrenched, possibly further accelerating inflation, but almost certainly making it much more difficult to stamp out.

Despite energy prices having moderated in the past months, inflation is going out of control in Europe. Negative demographics— including “the great resignation” (people falling out of the workforce far faster than normal)–means that wage pressures are extremely high, which feed into inflation in services. We are rapidly approaching the point where inflation expectations become entrenched, possibly further accelerating inflation, but almost certainly making it much more difficult to stamp out.

While extreme seasonal warmth in most of Europe has helped moderate energy prices over the past few months, an extreme cold snap could easily swing energy prices in the other direction, further accelerating overall CPI. Europe is in a particularly hard place with respect to fighting inflation, because of exceedingly high debt levels on the periphery (Italy, etc.) and high leverage exposure of its major banks (which hold risky Government debt as supposedly “safe” assets).

In the US, a major impetus to inflation is the labor market situation. Most people think that the recent high number of layoffs should dampen inflation. But there have also been massive numbers of retirements and early retirements; hence, the number of unfilled positions remains stubbornly high. It is ultimately the lack of ability to fill vacant positions, not the number of layoffs, that drives wage inflation.

The US saw high inflation in 2022 despite a huge appreciation in the US Dollar, a strong inflation moderating influence. The recent decline in the US dollar may now further fuel inflation, particularly if dollar devaluation continues in 2023.

b, Interest rates likely to remain high or go higher

The ECB has done too little too late to raise interest rates over the past two years, and the above chart shows the result; hence for the foreseeable future European interest rates will by necessity play “catch-up”, and have nowhere to go but up.

In the US, the Fed continues to try to wipe out inflation by squeezing the economy—a strategy of “burning down the house to roast the pig,” as Economist Robert Solow calls it.

Or as Luke Groman says, “Volcker could do what Volcker did because he could break inflation before he broke the Federal Government’s fiscal position. Powell can’t.” The national debt is several times higher today (close to 130% of GDP) than it was in Volcker’s time (in the range of 30%).

c, The Swing to Recession—or Worse

So the US Fed is likely to continue tight policy—until “something breaks” (e.g. failure of bond markets, or pension funds, etc.) When that happens, we will revert to Quantitative Easing and even larger fiscal deficits. The scale may need to be so massive, that given already high debt levels, society’s confidence in fiat currencies may be shaken.

Even before “something breaks”, the world economy is already losing steam. The IMF recently warned that a third of the world may be in recession by 2023. It could be higher.

d, Strain on Financial Markets

2022 saw a very rare scenario — both US equity and bond markets declining in the order of magnitude of 20%–an annus horribilis for investors, pension funds, etc. – this despite US financial markets still seeming hopeful for a soft landing. Should it become apparent that a soft landing is not possible and corporate earnings reports increasingly miss forecasts, equity markets could see a further collapse. Now that global debt levels are higher, economic fragility is greater. And of course Covid and the Ukrainian War, together with many other pressure points in the world, from Taiwan to the Middle East, tend to increase volatility.

Given such drivers, an optimistic scenario would be that equity markets move horizontally in 2023; whichever directions market move, it is unlikely to be a straight line progression.

Happy 2023!

I see a continuation of some of the drivers I have been discussing in various articles over the past two years, namely (a) stubbornly high inflation, (b) to which Central Banks respond by keeping interest rates high or raising them further; which in turn (c) pushes most of the world into a recession (or worse, depression); (d) high interest rates and declining GDP growth strain financial markets. Let me address each of these in more detail. A twist of war (Ukraine, etc.), climate change (hurricanes, etc) and pestilence (Covid, etc. ) may contribute to high volatility.

a, Stubbornly high inflation

Eurostat has just released some extremely scary inflation numbers:

Exhibit 1: CPI without Energy, Eurozone, % Change from One Year Ago

Despite energy prices having moderated in the past months, inflation is going out of control in Europe. Negative demographics— including “the great resignation” (people falling out of the workforce far faster than normal)–means that wage pressures are extremely high, which feed into inflation in services. We are rapidly approaching the point where inflation expectations become entrenched, possibly further accelerating inflation, but almost certainly making it much more difficult to stamp out.

Despite energy prices having moderated in the past months, inflation is going out of control in Europe. Negative demographics— including “the great resignation” (people falling out of the workforce far faster than normal)–means that wage pressures are extremely high, which feed into inflation in services. We are rapidly approaching the point where inflation expectations become entrenched, possibly further accelerating inflation, but almost certainly making it much more difficult to stamp out.

While extreme seasonal warmth in most of Europe has helped moderate energy prices over the past few months, an extreme cold snap could easily swing energy prices in the other direction, further accelerating overall CPI. Europe is in a particularly hard place with respect to fighting inflation, because of exceedingly high debt levels on the periphery (Italy, etc.) and high leverage exposure of its major banks (which hold risky Government debt as supposedly “safe” assets).

In the US, a major impetus to inflation is the labor market situation. Most people think that the recent high number of layoffs should dampen inflation. But there have also been massive numbers of retirements and early retirements; hence, the number of unfilled positions remains stubbornly high. It is ultimately the lack of ability to fill vacant positions, not the number of layoffs, that drives wage inflation.

The US saw high inflation in 2022 despite a huge appreciation in the US Dollar, a strong inflation moderating influence. The recent decline in the US dollar may now further fuel inflation, particularly if dollar devaluation continues in 2023.

b, Interest rates likely to remain high or go higher

The ECB has done too little too late to raise interest rates over the past two years, and the above chart shows the result; hence for the foreseeable future European interest rates will by necessity play “catch-up”, and have nowhere to go but up.

In the US, the Fed continues to try to wipe out inflation by squeezing the economy—a strategy of “burning down the house to roast the pig,” as Economist Robert Solow calls it.

Or as Luke Groman says, “Volcker could do what Volcker did because he could break inflation before he broke the Federal Government’s fiscal position. Powell can’t.” The national debt is several times higher today (close to 130% of GDP) than it was in Volcker’s time (in the range of 30%).

c, The Swing to Recession—or Worse

So the US Fed is likely to continue tight policy—until “something breaks” (e.g. failure of bond markets, or pension funds, etc.) When that happens, we will revert to Quantitative Easing and even larger fiscal deficits. The scale may need to be so massive, that given already high debt levels, society’s confidence in fiat currencies may be shaken.

Even before “something breaks”, the world economy is already losing steam. The IMF recently warned that a third of the world may be in recession by 2023. It could be higher.

d, Strain on Financial Markets

2022 saw a very rare scenario — both US equity and bond markets declining in the order of magnitude of 20%–an annus horribilis for investors, pension funds, etc. – this despite US financial markets still seeming hopeful for a soft landing. Should it become apparent that a soft landing is not possible and corporate earnings reports increasingly miss forecasts, equity markets could see a further collapse. Now that global debt levels are higher, economic fragility is greater. And of course Covid and the Ukrainian War, together with many other pressure points in the world, from Taiwan to the Middle East, tend to increase volatility.

Given such drivers, an optimistic scenario would be that equity markets move horizontally in 2023; whichever directions market move, it is unlikely to be a straight line progression.

Happy 2023!