Monetary policy over the past few years has been the most accommodative in the history of financial markets.

The US Federal Reserve has been purchasing about $80 billion in US Treasuries and $40 billion in Mortgage Backed Securities per month, with the European Central Bank and other major central banks following similar policies.

The US Fed has now changed the game. Recently released minutes of the September Federal Reserve meeting indicate that by mid-November, the Federal Reserve will begin to taper bond purchases– by US $10 billion in bonds and $5 billion in mortgage backed securities per month. This would imply completion of tapering by mid-2022, after which the Fed might choose to raise its benchmark interest rates. Similarly, Bank of Canada recently announced its intent to reduce hyper-accommodative monetary policy.

Bond purchases drive the price of bonds up, hence yields and interest rates down, serving to prop up financial markets. The concern is that by tapering bond purchases, interest rates may rise and financial markets may crash, as happened during the 2013 “taper tantrum”, compelling central banks to augment bond purchases to new heights, to prevent a full-blown recession or depression.

This article looks at (a) whether central banks are likely to succeed in this newest round of monetary tightening, or whether a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum is likelier; and (b) if we experience a taper tantrum, what is the fallback strategy for central banks?

a, whether central banks are likely to succeed in monetary tightening

On the first question, I am of the view that a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum is the likelier scenario.

History would judge today’s central bankers irresponsible if they did not at least try to wean the world from all this monetary stimulus, which creates a crazy world of negative interest rates, distorted economic signals—interest rates, the price of capital, are perhaps the most important set of prices in the economy.

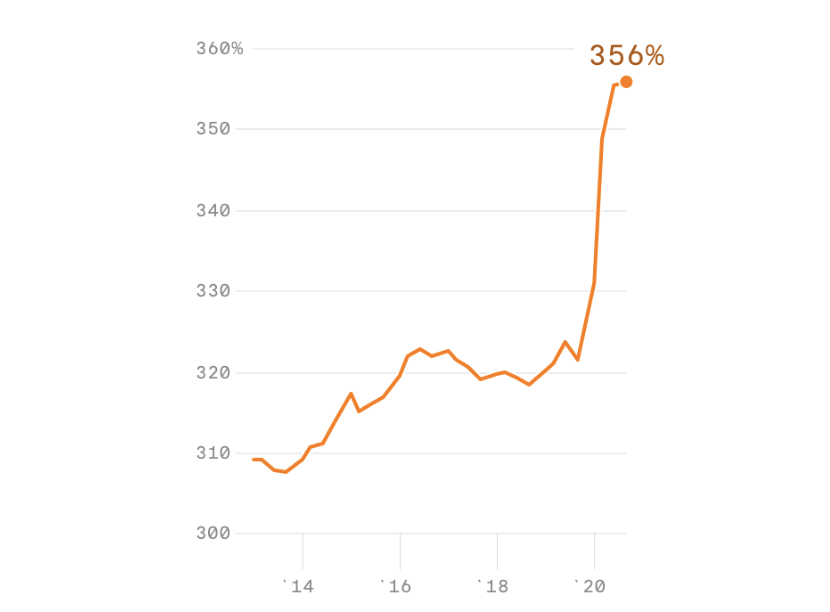

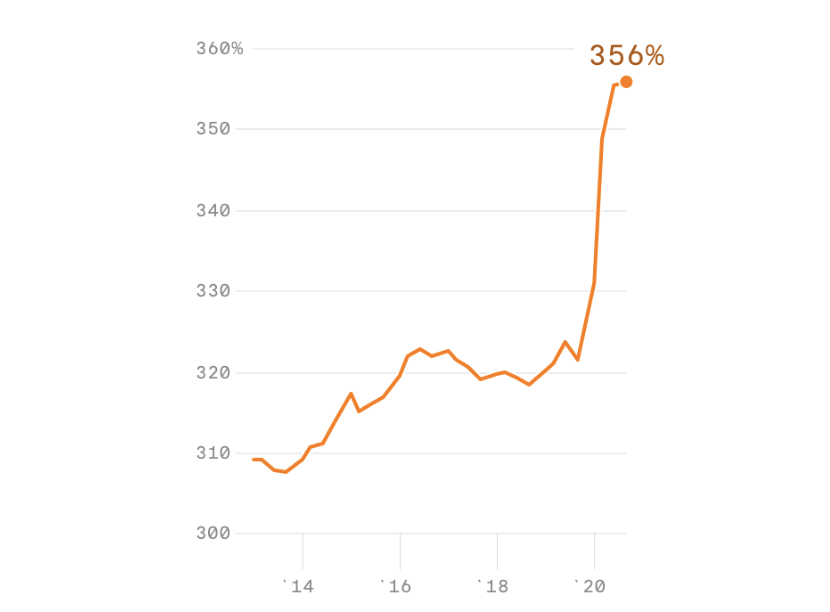

Why do I believe this latest balancing act of tapering will fail? Two very simple reasons: much higher global debt levels, and much higher inflation, than in 2013. As can be seen from the chart below, total global debt (Government, corporate and individual) has surged from below 310% in 2013 to over 355% in Q4 2021.

Exhibit 1: Global debt as a percentage of global GDP

Source: International Institute of Finance, Axios

Source: International Institute of Finance, Axios

The world today is less capable of withstanding higher interest rates than in 2013. Given the mountain of debt, even a modest rise in interest rates will squeeze corporate profits, trigger mortgage defaults and swell deficit spending by Governments, triggering at least a recession and a negative reaction by financial markets.

Inflation today is also in a very different place today compared to 2013. Whereas in 2013, inflation was well below 2% in the US, EU, and other developed countries, today’s inflation rates are closer to 5% and accelerating. Many central bankers are stretching the timeline of what they mean by “transitory”.

Let’s look at some of the largest price shocks hitting the world today:

b, the fallback strategy for central bankers The fallback scenario is financial repression. Under this scenario, central banks would perform whatever bond purchases are necessary to keep treasury rates at 4-6% lower than inflation, allowing Governments to inflate away the national debt.

This has been done successfully at various historic junctures in the past (e.g. in the US during the post-World War II decade). Financial repression is a form of institutionalized theft, with savers (e.g. anyone holding cash or debt, such as pensioners and pension funds) subsidizing borrowers (including Government).

In conclusion, both equity and bond markets are likely to experience headwinds in the coming months. At some point, when economies can no longer support higher interest rates, markets may experience a taper tantrum (resulting in a crash of both bond and equity markets). Having failed at weaning the world from monetary expansion, central banks may settle for a policy of financial repression.

Brace yourself for market volatility, followed by financial repression.

This article is for educational purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice. Investors should obtain their own financial advice.

The US Fed has now changed the game. Recently released minutes of the September Federal Reserve meeting indicate that by mid-November, the Federal Reserve will begin to taper bond purchases– by US $10 billion in bonds and $5 billion in mortgage backed securities per month. This would imply completion of tapering by mid-2022, after which the Fed might choose to raise its benchmark interest rates. Similarly, Bank of Canada recently announced its intent to reduce hyper-accommodative monetary policy.

Bond purchases drive the price of bonds up, hence yields and interest rates down, serving to prop up financial markets. The concern is that by tapering bond purchases, interest rates may rise and financial markets may crash, as happened during the 2013 “taper tantrum”, compelling central banks to augment bond purchases to new heights, to prevent a full-blown recession or depression.

This article looks at (a) whether central banks are likely to succeed in this newest round of monetary tightening, or whether a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum is likelier; and (b) if we experience a taper tantrum, what is the fallback strategy for central banks?

a, whether central banks are likely to succeed in monetary tightening

On the first question, I am of the view that a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum is the likelier scenario.

History would judge today’s central bankers irresponsible if they did not at least try to wean the world from all this monetary stimulus, which creates a crazy world of negative interest rates, distorted economic signals—interest rates, the price of capital, are perhaps the most important set of prices in the economy.

Why do I believe this latest balancing act of tapering will fail? Two very simple reasons: much higher global debt levels, and much higher inflation, than in 2013. As can be seen from the chart below, total global debt (Government, corporate and individual) has surged from below 310% in 2013 to over 355% in Q4 2021.

Exhibit 1: Global debt as a percentage of global GDP

Source: International Institute of Finance, Axios

Source: International Institute of Finance, Axios

The world today is less capable of withstanding higher interest rates than in 2013. Given the mountain of debt, even a modest rise in interest rates will squeeze corporate profits, trigger mortgage defaults and swell deficit spending by Governments, triggering at least a recession and a negative reaction by financial markets.

Inflation today is also in a very different place today compared to 2013. Whereas in 2013, inflation was well below 2% in the US, EU, and other developed countries, today’s inflation rates are closer to 5% and accelerating. Many central bankers are stretching the timeline of what they mean by “transitory”.

Let’s look at some of the largest price shocks hitting the world today:

- We are seeing a self-inflicted energy price shock caused by poor planning in transitioning to a green economy. Wind does not always blow, and the sun does not always shine: alternative energies today are singularly incapable of supplying base load energy. Meanwhile, capital expenditures to bring new fossil fuels on stream have diminished greatly. High energy prices are likely to stay, at least for the next few years.

- Two other major supply side bottlenecks facing the world today are microchips and shipping containers. Most experts maintain that it will take years for these bottlenecks to work themselves out of the system.

b, the fallback strategy for central bankers The fallback scenario is financial repression. Under this scenario, central banks would perform whatever bond purchases are necessary to keep treasury rates at 4-6% lower than inflation, allowing Governments to inflate away the national debt.

This has been done successfully at various historic junctures in the past (e.g. in the US during the post-World War II decade). Financial repression is a form of institutionalized theft, with savers (e.g. anyone holding cash or debt, such as pensioners and pension funds) subsidizing borrowers (including Government).

In conclusion, both equity and bond markets are likely to experience headwinds in the coming months. At some point, when economies can no longer support higher interest rates, markets may experience a taper tantrum (resulting in a crash of both bond and equity markets). Having failed at weaning the world from monetary expansion, central banks may settle for a policy of financial repression.

Brace yourself for market volatility, followed by financial repression.

This article is for educational purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice. Investors should obtain their own financial advice.